PHOTOS: MATTHEW TUFTS & CODY CIRILLO

"You don't want to go up there…the road is impassable and covered in ice!"

The unsolicited advice being shouted through a passing camper van's window was surreal and distorted, barely audible over gale force winds, blizzard conditions, and a mounting onslaught of head-on traffic descending the mountain pass. The Dutch tourist shook her head, rolled up her window and continued down the mountain.

Cody Cirillo motioned to his trip partner Matthew Tufts, who was cycling just up ahead, waving his arm to pull over, though he knew it was difficult to stop their momentum while climbing a 12-percent grade. They were already halfway up the pass, and road conditions were rapidly degrading. Cirillo pulled up beside him.

"What do you think? Should we turn around?" Cirillo said, almost screaming to get through the howling wind and engine rumbles.

"I think we go see for ourselves," Tufts remarked.

Cirillo knew this would be his answer, knowing Tuft’s ability to thrive in bad conditions. "We know snowy roads. Do they even know what we've been through?!"

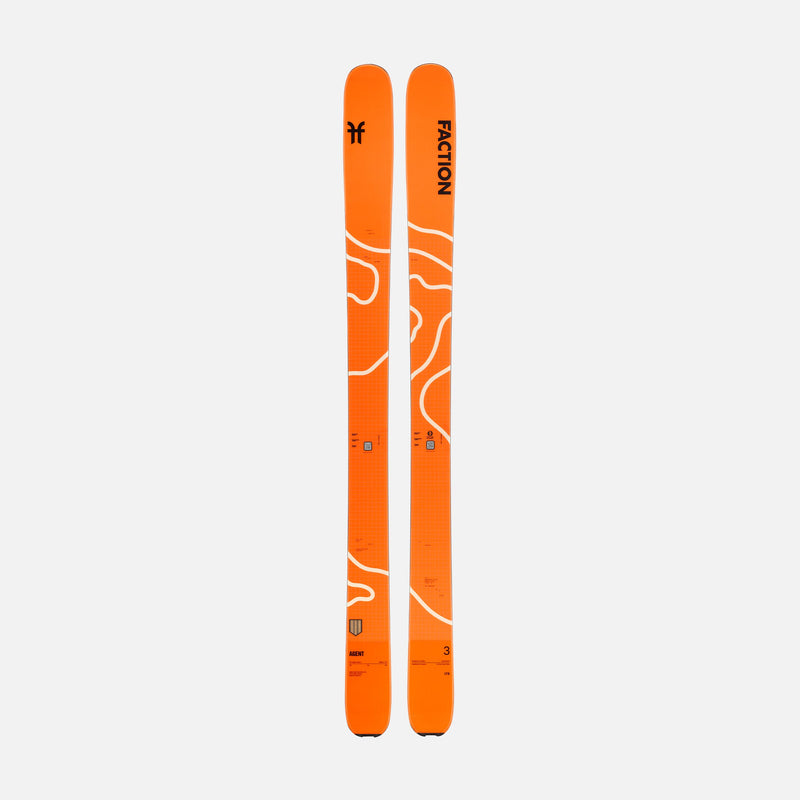

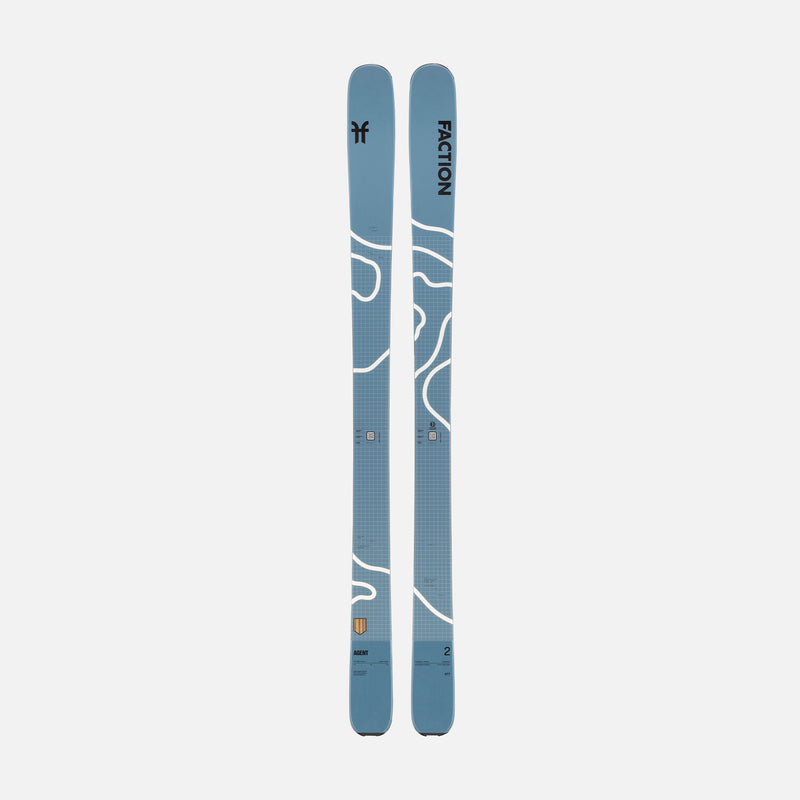

They hopped back on the saddles and prepared themselves for the impending doom promised. "Just one pedal at a time," Cirillo told himself, trying not to get blown over while hauling his 50-kilogram loaded bike up the pass. Strapped to each of their rigs were their Agent Series skis, waiting patiently for the descent they'd been promised after weeks of brutal riding.

With each pedal it got tougher. The grade steepened, the winds increased, the snow intensified. But just as it reached its worst, the sentiments among passing cars changed. Instead of calls to turn back, they were met with horns, shakas, claps, and thumbs up. Unexpectedly, the tide had shifted from worry to stoke. They were two underdogs prevailing against it all, while their unsuspecting audience watched safe and sound in the comfort of heated seats and four-wheel drive. They provided passing entertainment in the slow traffic, a movie scene right in front of their eyes. But like them, they too didn't know how it would end. They returned the shakas, and kept their cranks spinning toward Seydisfjordur.

This was Fjords of the Ring, a human-powered circumnavigation of Iceland's Ring Road in the depths of winter, where the only way forward was to trust the process and let the skis do the talking when conditions aligned.

In the summer of 2023, Cirillo approached Matthew Tufts, friend and photojournalist, with an idea: a circumnavigation of Iceland to ski its peak-laden fjords and experience its unearthly landscape. But there would be one major caveat: they'd be doing the entirety of the route, roughly 1,700 kilometers, on bikes, with all of their gear in tow.

The partnership made perfect sense. Cirillo and Tufts have been lucky to travel all around the world together with their skis. From Morocco's High Atlas to Chamonix's steeps and British Columbia's most picturesque pillow lines. Tufts is a renaissance man in its purest sense, one who lives for the story and brutal conditions. An appreciation for the experience and doing things the unconventional way. The longer and weirder, the better. He lived in a truck camper for years eating only oatmeal. He's sampled each of the Chamonix Valley's bakeries to crown the best pain au chocolait. He frequents the Southern Patagonian Icefield with unknown itineraries.

"If there was anyone I knew who would be interested in a questionably possible human-powered epic, it was Matt," Cirillo says.

The Ring Road, aptly named, is the main roadway in Iceland that runs just about the entirety of the country's circumference, stretching from the nation's capital, Reykjavik, to the northern Troll Peninsula, the eastern Land of Dragons, and the black sand beaches of the South Coast. The route connects a variety of the vast and unique geographies of the country.

Iceland has been painted as the land to chase waterfalls and the aurora borealis, to see puffins and bathe in the famous Blue Lagoon. It's a country that proudly markets itself as a stop-over destination, a land of bucket-list adventures and plug-and-play excursions. In the era of the influencer, this romanticized version of Iceland is beautiful and pretty momentary.

The decision to use bikes came from a similar philosophy to ski touring. There's a deeper connection to the place, a real purpose in the travel, a vulnerability that can't be matched. "It wasn't an environmental decision (I don't think flying half-way around the world with skis and bikes makes this an eco-trip by any means), but rather a means to slow down and to try to feel it all," Cirillo says. "And in the land of van-life from one volcano to the next, what better way to try and experience it than at a bicycle's pace."

For Cirillo, the ski setup was crucial. He chose his Agent skis for the expedition, a versatile touring platform that would need to handle everything from steep couloirs to variable coastal snowpack. Every gram mattered when the skis would spend much of the journey strapped to heavily loaded bikes, but they also needed to perform when conditions finally aligned for the downhill. Light enough for approach efficiency after exhausting bike days, stable enough for serious descents, versatile enough to handle whatever Iceland's unpredictable weather patterns delivered.

Tufts held onto Cirillo's bike frame as he searched through a bag of tools and parts, struggling to find the correct hex key for his handlebar screws. As a novice bikepacker, it was only his second time putting together a bike. The first was in his garage back home in Colorado, yesterday.

Record-breaking winds in Reykjavik kept them huddled in the fenced backyard of their hostel, alternating between holding each other's bike parts and keeping their cardboard bike boxes from ending up in the adjacent fjord. It was winter alright, and the fabled arctic storms that pummel Iceland made themselves known. If you were of sound body and mind, you'd likely decide that these conditions weren't conducive to biking, but with snow stacking up in the north, and their powder panic already setting in, they packed their panniers to the brim and got on the road.

With a delayed 6:00 P.M. departure, they navigated Reykjavik's suburban landscape, connecting sidewalks and a network of bike lanes to get out of the city. They took detours through neighborhoods and met a herd of Icelandic horses. Their two-wheeled galleons held steadfast into the winds, powered by the city's finest pastries, and the pure excitement that came from diving into the unknown. They were actually doing it.

Then came the first major obstacle. There are two tunnels in Iceland that bikes aren't allowed to go through. One is just outside of Reykjavik, the other near the northern capital of Akureyri. What could have been a casual 10 kilometer ride now forced a 70 kilometer detour, around the entirety of the fjord. So began their first of many detours.

"In the end, what's another 60 kilometers?" they chuckled.

As the sun set, their legs grew weary, and their initial excitement waned. To move a 50-kilogram bike was hard enough. Coupled with unrelenting headwinds, it felt almost impossible at times. Trepidatiously, they donned headlamps, called it quits for the day, and soon found a place to camp just off the road.

"We were almost silent during dinner… A heavy, unspoken feeling of, 'Whoa, we may actually be in over our head this time,'" Cirillo recalls. "Still over 1,600 kilometers to go."

Their journey north only got more difficult. Soaked to the bone from wet snow, a constant barrage of headwinds and crosswinds that thrice blew Cirillo off the road, camping in ditches, frozen toes, and ice roads without studded tires. That first day had seemingly set the tone. To earn it, they'd have to endure. They had chosen this method to "feel it," and they were feeling it alright. Well, everything except their toes.

The skis remained strapped to their bikes through it all, a constant reminder of why they were suffering through the brutal approach. The Agents became part of their identity on the road. Heavily rigged bikes, blinking lights, camera equipment, camping gear, and most notably, touring skis mounted on loaded panniers cycling through an Icelandic winter. They'd become a spectacle.

They topped out on the mountain pass just beyond Bifrost, another blizzard bringing their pace to a crawl. Heads down, pedaling through it, snow coating every inch of their bodies. A group of Italian skiers with their flashers on pulled up next to them, windows down, phones recording.

"We'd become a spectacle on the road. It makes sense with our heavily rigged bikes, blinking lights, and skis, of course. But regardless of our baggage, bikepacking in the Icelandic winter? That was what really stood out," Cirillo says.

A few long days in the saddle later, they made it north to the famed Troll Peninsula where they could finally start the skiing portion of their adventure. "We joked that we were simply paying the 'troll toll' the entire way there. Hopefully our payments were enough, and we did the currency exchange correctly," Cirillo laughs.

They were welcomed to Sóti Lodge, an old schoolhouse turned unassuming adventure basecamp just outside the northernmost town of Siglufjordur, by owner-operator-matriarch-legend Ólöf Ýrr Atladóttir. Tonight, a hot tub, cold beer, and home-cooked arctic char on the menu. They happily turned down their usual roadside jet-boiled tortellini, parked their bikes, and settled in. After hundreds of kilometers of brutal riding, they'd earned this respite.

But the weather had other plans. Touchy avalanche conditions and socked-in, stormy weather kept their first few days of ski touring limited. The Agents stayed strapped to the bikes, waiting. Iceland and its rugged northern coast are susceptible to arctic storms and ever-changing winds, a place where the forecasts are hard enough to predict, let alone get right with any precision.

During their down time at Sóti they found ski guides Helgi and Andres, Ólöf's son, glued to the Icelandic national weather app. "Þetta reddast," Andres said. He explained to them that it's a traditional Icelandic motto, a positive take on "It'll all work out." They had to let go and trust the process.

The phrase would become a mantra for the rest of their journey. In a trip defined by uncertainty, unpredictable conditions, and moments that required total faith in the process, Þetta reddast captured everything they'd come to Iceland to learn. "It's not about driving around and ticking lines," Cirillo would later reflect. "It's about being connected to these environments, not just taking from them, but trying to understand and learn from them."

The following day they bid Sóti adieu, and got back on their bikes. It was another weather day for them, gray skies and cold temperatures. They planned only to set up camp just before Siglufjordur, which was around the tip of the fjord. They stopped at a gas station to collect food for the night, but as they had begun to learn about Iceland's off-season, opening days and hours are as unpredictable as the weather. It was closed and they were out of food. Provision-less, they'd need to push to Siglufjordur.

As they crested the northernmost point of the peninsula, they came to a screeching halt. On their left, a perfect Wes Anderson-esque orange lighthouse. On their right, the sun had worked its way through the clouds, giving light to a perfect, 800-meter couloir with snow right down to the road.

"Open mouthed, gleaming with excitement, Matt and I knew it was on," Cirillo remembers. "In a matter of minutes our bikes were laid against a mailbox, our cleats swapped with ski boots, and we started booting directly up the couloir."

Finally, after 500 kilometers of riding, their Agents came off the rack. This was the moment they'd been waiting for, the reason they'd endured frozen toes and gale-force winds and countless hills. The skis felt light in their hands after days of hauling them on the bikes.

They pushed up the behemoth with ease. Seagulls flocked overhead, the soft snow beneath their ascent plates felt stable. No more than two hours later they were at the top, a softly glowing everlasting sunset stretched across the dark ocean, and their bikes sat idly below.

Cirillo dropped in first. "The snow was far from perfect, a mix of windboard, ice, and boot-top powder. But, the location, the timing, how we had just ridden our bikes 500 kilometers to get there. It was all surreal. It was the best run of my life."

Their skis performed flawlessly. Despite the variable conditions, the mixed snow surfaces, and the technical nature of the line, the skis delivered exactly what Cody needed. They carved through the windboard, floated in the deeper pockets, held an edge on the ice. After two weeks of waiting, strapped to a bike and covered in road spray, the Agents proved why they were the right choice for this expedition.

Þetta reddast indeed.

They spent the next week ticking lines off all across the Troll peninsula. The Agents saw action day after day, each tour revealing new aspects of Iceland's unique terrain. They met up again with Andres, toured the local ski hill to access terrain off its backside, made their way down the rarely skied north-western face of "The Horse" and other looming peaks in Siglufjordur. They discovered new lines next door near Olafsfjordur.

"The Troll Peninsula is a ski-touring paradise," Cirillo says.

But in pure Icelandic fashion, their window was only momentary. Southeastern winds known as the "hair-dryer" came in fast and brought warm temperatures, flushing snow from the surrounding slopes. Seemingly overnight it became spring in the north. They knew it was time to venture onward.

They took the long and lonely road east with the winds against them, per usual. Another un-rideable tunnel, another roughly 70-kilometer detour just outside of Akureyri. They counted days by the amount of tortellini eaten and how tired they got of the delusional jokes they made to each other during the slog. They questioned whether or not they had started to lose their minds. Monotony seems to bring out the weirdness.

The skis on their backs became a beacon of hope during these grinding days. Each pedal stroke was an investment in the next line, the next moment when they could swap cleats for boots and let the Agents run free on another Icelandic descent. That slower timing, that vulnerability, it opened them up to what was actually there.

They spent the next week ticking lines off all across the Troll peninsula. The Agents saw action day after day, each tour revealing new aspects of Iceland's unique terrain. They met up again with Andres, toured the local ski hill to access terrain off its backside, made their way down the rarely skied north-western face of "The Horse" and other looming peaks in Siglufjordur. They discovered new lines next door near Olafsfjordur.

"The Troll Peninsula is a ski-touring paradise," Cirillo says.

But in pure Icelandic fashion, their window was only momentary. Southeastern winds known as the "hair-dryer" came in fast and brought warm temperatures, flushing snow from the surrounding slopes. Seemingly overnight it became spring in the north. They knew it was time to venture onward.

They took the long and lonely road east with the winds against them, per usual. Another un-rideable tunnel, another roughly 70-kilometer detour just outside of Akureyri. They counted days by the amount of tortellini eaten and how tired they got of the delusional jokes they made to each other during the slog. They questioned whether or not they had started to lose their minds. Monotony seems to bring out the weirdness.

The skis on their backs became a beacon of hope during these grinding days. Each pedal stroke was an investment in the next line, the next moment when they could swap cleats for boots and let the Agents run free on another Icelandic descent. That slower timing, that vulnerability, it opened them up to what was actually there.

After a few hundred miles of riding, they descended to Egilstadir, the largest town in the East. From here, they could start going back South, finally passing the halfway mark of their adventure. But they had other plans. This time a self-imposed 70-kilometer detour to the eastern fishing village of Seydisfjordur.

Seen in "Secret Life of Walter Mitty," it's located just over the big mountain pass that Ben Stiller’s character famously longboards. But beyond the Hollywood allure and quaint sea-scape vibes, what attracted them to it was the potential of a ski line. Deep in the back of an old ski-touring photo from the area, Cirillo had seen a couloir. They didn't know if there was snow, or if it was possible. If they wanted to find out, they'd have to painstakingly bike there.

"But if we learned anything from the last 25 days, sometimes you just need to trust your own timing and to go see for yourself," Cirillo says.

This was the pass where the Dutch tourist had warned them to turn back. This was the 12-percent grade where passing cars had transformed from concern to celebration. And somewhere beyond Seydisfjordur, perhaps there was another line waiting, another moment where the Faction Agents would prove their worth. The skis had already endured being strapped to loaded bikes through blizzards, covered in road spray, subjected to dramatic temperature swings from coastal humidity to arctic cold. They'd performed in every condition Iceland threw at them: wind-affected surfaces, variable coastal snowpack, boot-deep powder in protected zones, technical couloirs with mixed conditions.

Their Agents were part of the story, visible in every interaction on the road, present in every conversation about what these two cyclists were actually attempting. When locals asked about their journey, when tourists stopped to take photos, when passing drivers honked their support, the skis told the story before words could.

"When you're that remote and that committed, you need equipment you can trust absolutely," Cirillo explains. "Our Agents were perfect for the mission. They became part of our identity out there."

The versatility proved essential. On any given day, they might encounter a 1,000-meter boot pack after already riding 50 kilometers, requiring skis light enough to not break them. Then the descent might offer anything from champagne powder to windboard to bulletproof surfaces, requiring a ski stable and precise enough to handle it all. The Agents delivered on both counts, every single time.

For Cirillo, the skis represented something deeper than just performance metrics. They were a tool that enabled connection to place, that allowed him to engage with Iceland's landscape in the most intimate way possible. By choosing to travel slowly, to earn every descent with hundreds of kilometers of riding, the eventual moments on skis became transcendent.

Watch Cody and Matt's Iceland bike-to-ski adventure in their film “100 Words for Wind”. Discover the Agent Series and explore the complete touring range here at factionskis.com.